How to ‘Test and Learn’ in service design

Back in late 2024, Pat McFadden (the Minister for Intergovernmental Relations of the United Kingdom) outlined ambitions for the reform of the state in the UK by using a test and learn approach.

This marks a global shift more broadly I’ve been hearing from organisations. How can we take a different approach to delivering better and make our services more efficient to deliver? But do this in a more iterative way where it’s not a large scale transformation project.

I was really pleased to hear this. Test and learn for me is central to my practice. As a designer, who started out making products, I would prototype designs using different materials, and test these with users. I was always curious to learn if how I intended my design to be used, was how someone else would use it. Now as a coach, teacher (and filmmaker) I do the same.

As a product designer, I prototyped things with my hands. After researching and developing an idea, we’d sketch concepts, bending wood, shaping metal, and folding paper, constantly changing the design. Move the on/off button here, make that curve slightly bigger, change the wording on that screen.

As I moved into less overtly physical forms of design practice like service design, we would test if what we had created would help users to reach the outcome we intended. Rather than one single interaction with a product, we had to consider the whole experience.

In the images above, you can see the process of me prototyping a rental bike scheme for Glasgow in 2008, exploring physical and more invisible elements of the service. Don’t judge the user interface too much, we were in the very nascent days of good UI design..

For me, at the heart of this test and learn approach was always a readiness to observe, learn, adapt the design, and repeat. Until you were satisfied, what you designed helped a person do the thing they wanted to do, and what you intended.

As a principle, testing your idea and learning about how to improve it is the same whether it’s helping someone to hang up clothes better, or helping a young person prepare for a job interview.

I spent my career as a strategic designer helping organisations to understand the needs of their users, balance this with their intent and then to prototype ideas to deliver on this, before investing in delivering that at scale.

Instead of using the term prototype (which made little sense outside of a product context at the time) we talked about testing and learning. It really seemed to land and push back on 20th century waterfall management processes.

Back to McFadden’s speech. It is always great when an approach that really makes common sense is championed by leadership. Particularly when it goes against the established mindset of needing to know exact certainty at every step of the design process.

In the speech, McFadden talked about witnessing a test and learning culture, freeing up teams to be more honest, to make mistakes, and ultimately to roll out services that actually work. That's the most important part. Test and learn really is a mindset, and a practice, that can (and should) become part of the culture and approach to everyday work. Top to bottom of any organisation.

But, it’s not as simple as saying just do it like Uber or Airbnb or any other large, internet native company. Services come in lots of shapes and sizes. Some predominately digitally delivered, some more relational and supported by smaller technology platforms. Some commercially focused with outcomes to increase profit, others with intentions of delivering good things that support our society to thrive.

Testing and learning seems more challenging when it comes to whole services where there may be multiple moving parts that stretch across teams or organisations. So how do we take a ‘test and learn’ approach to services with all their complexity?

Now feels like a good time to recap on, step by step, how we take a test and learn approach to whole services. If you’re interested in a deep dive on this, I run an agile service design course twice a year, but for now, let’s start with:

Understand your scope

Choose the right fidelity level

Test your riskiest assumptions first

Be clear about what success looks like

Test for long term change (not just short term)

1. Understand your scope

Are we researching and designing a new offer that helps someone do something, or are we designing how that offer is delivered? The scope of our work changes the nature of our testing and what learnings we can put into action. Service design has two ‘modes’. In the first, we think about what we’re trying to achieve and what the service needs to do to deliver that outcome, and in the second we think about how that service needs to work to achieve those outcomes. This is what I like to call the ‘what and the ‘how’ of service design. When we’re iterating a service and ‘testing and learning’ we might be focussed on one more than the other.

What and How of Designing a service

What: The offer, the value proposition, the intervention

How: The steps you use it in, what channels it exists on, its brand, the design of the touchpoints a user interacts with

Testing ‘the what’: An offer, intervention or ‘product’

If my intention is to help parents feel less stressed, I might want to test what might help them. Meals on wheels, free childcare, therapy, a personal massage. We might call this the offer, the value proposition, then intervention… depending on which sector you’re working in. These might not all help reach the intended outcomes. In this frame, what I’m not testing, or at least focusing on, is how to book that product or service, onboard, the experience. I’m focused less on details.

Testing the ‘how’: The steps, the journey, the touchpoints

If I am designing the how, which is how that offer is delivered, I am focusing much more on the detail of delivery. The order of steps, the design and accessibility of each touchpoint or interaction in that service for users, how feasible the technical and operational delivery of that service is.

Sometimes, these are tested together, but when I’m designing and testing the ‘what’, I’m trying to avoid getting caught up in testing detailed ‘how’ insights that could distract us.

Testing your offer (the what) and how it’s delivered (the how)

In 2017, the team at Snook, led by the marvelous Charley Pothecary, worked on testing a hypothesis for a housing association. They had an idea that they might be able to identify residents who were exhibiting signs of vulnerability via their outsourced repair teams. Residents then could be provided with additional support pathways by key workers and the housing association.

Vulnerable is a vast term that applies to lots of different contexts. In early preparatory work, the housing association had done some research and development of different types of vulnerability definitions, key signifiers, and what kind of increased risk this might have on individuals in their care. For this project we were focusing on vulnerabilities like memory loss with indicators like not eating delivered meals, and other risks, like extreme hoarding.

Repair System logging jobs, photo from short discovery research

Early research told us that repair teams often felt guilty going home and not having somewhere to report concerns they had about residents they considered vulnerable.

We were given a small budget to test the idea to test the ‘what’ - what could we do to identify more vulnerable residents? Could repair teams identify genuine vulnerabilities that could be confirmed through follow up with key workers? The idea that they could was still uncertain without testing.

To test this we used an approach called hypothesis driven design where we collaboratively write our idea for the ‘what’ as a hypothesis that we can then test.

This is a great approach for testing the ‘what’ of service design when there is a strong opinion-led idea that needs to be tested, but where discovery research is not an option (as is sometimes the case when work is scoped incorrectly). In this case, there was evidence of repair teams asking for support in order to highlight concerns they had, but we didn't know if this would work, or be the most effective way of identifying vulnerabilities in residents.

This is the hypothesis we wrote to test the idea:

We believe that

We can scale our ability to find residents who need support by asking our repair teams if they have spotted any signs of vulnerability or have concerns about residents welfare

To find out if this is true we will…

Train a small cohort of repair teams in the signs of vulnerability and add a short set of questions on the end of their repair logs

And measure…

If we receive reports of vulnerable residents or welfare issues and if these can be confirmed as genuine and currently undocumented over a period of 2 weeks by our internal key workers

We are successful if…

We receive reports on residents from our prototype and identify genuine vulnerable residents

Writing an idea like this helps us to collaboratively agree as a team what idea we’re testing and importantly, agree on the criteria of success for that idea. This helps to create a ‘safe space to fail’, when an idea doesn't work out the way we thought it would. All of which is great, but how do you test a hypothesis like this?

For this, a paper prototype wouldn’t cut it. We wanted to genuinely see if repair teams would remember to log, what they would log and how they might feel about this. This needed elements of an experience prototype, where it feels a bit like the real thing, and future users can interact with it.

Basic interactive Typeform prototype

The team ran a light-touch vulnerability training session with the repair teams, and produced a prototype ‘vulnerability identifier’ tool using Typeform that would be filled out at the end of every repair log. We synced these repair logs with the case numbers used by key workers to log vulnerable residents, and then had our key workers review if each person was already being supported or not.

We built just enough of the ‘what’ of this service to test whether it was a good idea for repair staff to identify vulnerable residents, but no more. A simple type form and some back-end data matching was enough. In three weeks we received;

75 new reports in two weeks from 6 operatives.

From these 75 reports, 4 new vulnerable residents were confirmed as needing further support.

Each report took only 55 seconds to complete, which was vital as the time of repair teams was limited from job to job.

With this positive outcome from testing, we gained further approval to develop an improved prototype. This is where we moved into testing more of the ‘how’, spending 3 weeks co-designing a more detailed service with repair teams. This work helped us understand how to make the photographs we’d used to spot vulnerabilities more understandable and brought up themes we hadn’t considered like how to document concerning behaviour in shared landing spaces, when they could only log a report using our initial prototype to an individual house.

Refining the how of the service through co-design sessions

Testing in-situ like this will help you find out about challenges you hadn’t considered or might have missed in research.

With more successful testing, we were then given further budget to explore a detailed design and consider the mechanics of linking two different systems up between the repair teams software and the housing association’s internal log, led by the brilliant Mathew Trivett.

We also worked with legal advisors to explore the ethics and impact of privacy and the upcoming GDPR law being implemented in 2018. This involved reviewing and checking the agreements in place around personal data, users' residential contracts (residents had already agreed for interventions and pathway offers to be made to them in the event of an observed issue in their home).

What started out as a preconceived idea was first broken down into hypotheses, then tested. First we tested the ‘what’ of whether we could or should identify vulnerable users with repair teams, then after establishing this, we moved on to test how we might do this. It’s really important to work out what ‘scope’ you’re working in when you're designing a service - have you been asked to look at just the ‘how’ and not the ‘what’, or is it all in scope? If you have been asked to just review the ‘how’ this can be frustrating, but writing the idea down as a hypothesis and agreeing some success criteria with your stakeholders can be a really helpful way of bringing this up in a way that needs minimal confrontation.

2. Choosing the right fidelity

When I’m testing something, I’m always looking for a sweet spot of what is a fast, cheap way of testing that will give me the most insight, but also not cause harm! This means, not spending too much time making a really slick prototype, but just interactive enough for us to understand if what we intend through the design will result in what we hoped for.

When choosing how to test our service or elements of it, we want to think about fidelity. How detailed should our prototypes be, and how much of the service should we test? How accurate should it be to the ‘final thing’?

It’s not always the case, but usually the more interactive a prototype, the more expensive and slow it will be to make. Sometimes, we don't need something super detailed to test an idea (as we saw with our housing example). We can also find that the more effort we put into our prototypes, the less likely we become to want to change them.

We have to make a decision on what is going to help us learn the most with the resources, time and permission we have.

If we go for a low-fidelity (less detailed) basic paper prototype, it’s likely we can have an informed conversation about a design, but it might not really test how a user would interact with it. If we develop something that’s really high-fidelity (a detailed prototype), we may risk spending lots of time perfecting a bad idea. So we have to choose fidelity wisely.

A cardboard prototype using Wizard of Oz techniques for an interactive museum experienced. Humans hiding behind the cardboard respond to user inputs and prompt with fake audio announcements

This is where I think we can get really creative. There’s a technique called Wizard of Oz where we simulate the behavior of a computer and its responses to a user. The name of the experiment comes from L. Frank Baum's 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, in which an ordinary man hides behind a curtain and uses "amplifying" technology to pretend to be a powerful wizard. If we’re testing elements of how a service is delivered, there are a plethora of tools out there like ifthisthenthat where we can mock up most automated digital elements of services. These days we can pretty much fake lots of types of service interaction.

If we’re designing more relational services, where people interact, we can test small parts of this service to understand responses. This might be a phone conversation, a check-in between a support worker and a service user, a welcome at a reception, a counselling session. We can mock those services up and play the role, test the phone script, and respond as a customer service agent. In certain sessions, work with professional roles to test their delivery, particularly where ethical guardrails are in place.

Back in the mid 2010s, Emma Parnell and Charley Pothecary at Snook, worked with the Government Digital Service in collaboration with Open Identity Exchange and high-street store Timpsons to test a an offline offer to verify people’s digital identity. This was focused on users who may have failed to verify themselves online due to using the wrong I.D or struggling with using a digital channel of the service.

Experience Prototype setup inside a Timpsons Store

Initially it was proposed that we test the new I.D verification service in a lab, but we quickly realised this wouldn't work. Timpsons are readily available on most high streets and some large out-of-town supermarkets, but they’re also noisy environments where keys are cut and shoes repaired. We needed to ensure we tested the whole experience, end-to-end inside an actual store.

Instead of testing the I.D verification product in a lab, we brought the whole service to life with a series of touchpoints that had ‘just enough’ interactive features.

The core of our prototype was set up in store, with a trained Timpsons employee to use their identity verification software their sister company Arkhive had developed. The prototype was super low-fidelity, mostly wireframes that could just get through a simple user flow of the software at the time, but we also tested what it was like to travel somewhere to set up your digital identity in a busy ‘shop’ environment with someone handling your personal data and documents inside a potentially busy store.

We had permission to film the experience and interview the person testing the service after the experience was complete.

Overall, we had good feedback with 13 out of 16 users stating that they were comfortable with providing identification documents in store. However, we still encountered some issues of trust;

“I feel most uncomfortable when the Timpsons staff take my documents out of sight, I worry about identity theft”

When we’re prototyping services, it’s vital that we test these experiential elements.

Are there areas users are more likely to encounter something that risks their safety? Or does our service rely on a strong sense of trust with our users? If the answer is yes, we need to test for that, so we did.

Learning that our users were struggling to trust in-store staff meant that we needed to build that trust earlier in the process, so we changed the first email sent to users inviting them to visit a store to include information about how documents are handled in store and kept in sight at all times. We also changed the training for in-store staff to make sure they shared the screen they were using with users and give that user the opportunity to view what was being documented.

This type of testing told us much more than an in-lab prototyping would allow us to.

13 out of 16 might seem like a good result, however if we consider the potential users of a service like this might include those who don’t have access to the internet (5% of the UK population), we could be looking at around 600,000 people. Add to this those who don’t have essential digital skills and other groups including those who choose to stay offline and we’re looking at a sizable user group. So, it’s important to test and learn important details that can improve usability and take up.

A staff member running the Experience Prototype

In this case, the fidelity of an experienced prototype felt right. Further down the line we could have moved back to paper prototyping to test the content in the first email we would send to people inviting them to a store, to see how confident they were on knowing what to do, or what type of I.D to bring or whether they trusted the service. But without testing in-situ, we would never have learned what we did.

The word fidelity can be traced back to the Latin word ‘fidēlis’, meaning "faithful or trustworthy." When you’re thinking about the fidelity of a prototype, you need to create something that your user can trust as a real reflection of the service and your team will trust the results of when it’s tested. Choose your fidelity wisely.

3. Test your riskiest assumptions first

When we’re designing whole services, we can’t test everything. Sometimes due to time or available funding we have to move forward without testing every element of a design. Thinking about testing the ‘what’ then the ‘how’ will help, as will choosing the right fidelity for your testing, but when we have limited resources we need to prioritise.

That means focussing our testing and learning on the areas of our service where we will get the most value from that testing; our riskiest assumptions.

What do we feel the least confident about? And what do we need to learn in order to feel confident moving forward in our design and development process. Also, what can we test later as we build something?

Sūryanāga Poyzer wrote a brilliant blog post about how to prioritise and score your riskiest assumptions. I agree, we have to consider what we’re least sure about. Like Sūryanāga, I think about testing our assumptions from three angles:

Users: What are we least sure about how users will behave, interact or choose to do something?

Organisationally: Can the organisation or collective deliver this thing. Testing to figure out if our organisation is resilient to contact, sudden spikes in demand, users straying off our intended path we’ve designed. This includes any policy or legislative constraints, can we really not change the way this is done?

Technically: Can our intended design be realised? Will our systems manage the amount of users? Can we make these two systems talk to each other and share data?

It’s important we look at our assumptions in all of these three areas when we test and learn. Overlook one area and we could easily end up with a service that doesn't work.

Snapshot of user research by the team on why people weren’t claiming Free School Meals

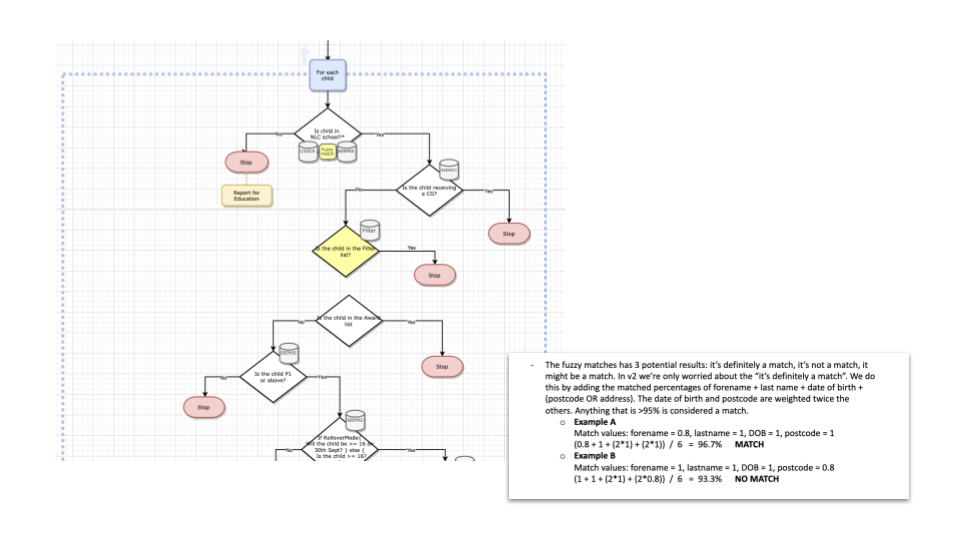

Pre pandemic, Snook worked on finding a way to increase the uptake of Free School Meals with a local authority in Scotland. The project was spearheaded by the brilliant Anne Dhir, amazing technologist Marek Bell, and superstar designers Linn Cowie-Sailer and Greg Smith.

Although there were lots of ways to improve uptake from better meals to making the form to apply slightly easier to use, we felt the opportunity to remove applying completely and auto-allocating meals would be a good solution. This felt right given local authorities already have the data they need to identify who is eligible for benefits. The problem was that data was stored in three different places, and those systems did not talk to each other.

So we worked on developing an auto-benefit allocator, focusing at first on Free School Meals, later on other grants and benefits.

Testing matches on data to auto allocate free school meals

The riskiest assumption for us was technical. Will the algorithm we’ve created, with the data we have blended together, be able to accurately identify citizens in that geographic area who are entitled to Free School Meals (and other benefits)? The goal was to increase the take up of benefits that local citizens were eligible for and reduce the indirect cost on them, for example the administration of filling in forms.

We spent more of our time and budget testing if the algorithm and machine learning approach we created could result in real matches as if that didn’t work, the design would not be feasible. This was our riskiest assumption.

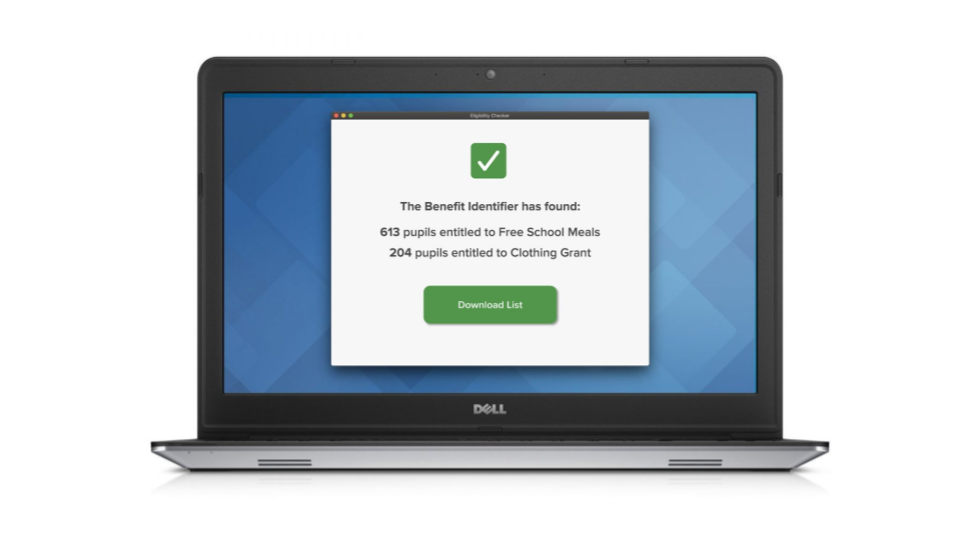

Results from testing the benefits identifier

Early results proved really fruitful. After implementing the design, between June 2018 and April 2020, the number of pupils registered for free school meals in North Lanarkshire Council increased by 2,275 or 21% and the approach was extended to clothing grants, increasing uptake by 7%.

We can’t always test everything. We can use our experience to know what might work and really test the riskiest things in our proposed designs as early as possible. We should continuously test as we build products and services and this gives us space later on to test and refine other elements, but in earlier stages, test the riskiest assumptions.

4. Be clear about what success looks like

So often when I see a test and learn approach go wrong, it's because a team hasn’t been clear about the outcomes they want to achieve before they start.

Often we think about one aspect of our intended outcomes at the sacrifice of all of the others. We might think for example that we want to reduce the cost of our service or deliver a better outcome for staff, but we haven't considered what success looks like for users. As Lou said in Good Services, “a good service is good for users, staff, your organisation and the planet” if our service doesn't work for one of these groups, it’s simply not going to work.

When we’re setting out to prototype and test and improve our service, we need to think about what success looks like for our users, the organisation and the policy or regulatory environment we’re working to, to ensure it is met if relevant.

It can be hard to think about success for these groups at a high level without getting lost in an existential tail spin, so I like to collaboratively map what success looks like for each group at each stage of a service, then take a step back and look at what this means for the whole service. We might, for example, have a user that needs to be able to know what to expect before using a service, or a staff member that needs to be able to give an answer quickly. With these outcomes mapped, shared, memorable, and measurable, it means everyone involved in the design and delivery of that service can coalesce around striving to achieve that.

When we look back at each stage of our user’s journey using our prototype, we can then ask things like:

Did users feel confident in what they needed to do next?

Did users receive confirmation they had an appointment?

Did they trust the service at this stage?

Did the organisation have data on who is selecting which pathway in the service?

Did we ensure only eligible citizens moved forward in the service?

Did we give out the license?

So whatever prototype you run, make sure you have clear criteria of what success looks like for your user at each stage of using the service. That way you can test whether what you've built really delivers what it needs to for everyone.

5. Test for long term change (not just short term)

Most established prototyping approaches tend to focus on the transactional elements of services that happen in the here-and-now. There’s a big A/B testing culture out there that encourages us to compare and contrast designs that have small differences with users to see what works best.

Traditionally, this has been used for testing user interfaces, and expanded to other easy to contrast designs of things like two bills, or letters. It’s similar to randomised controlled trials but these tend to expand beyond user interfaces, having 2 or more trial groups in which everything is the same except for the thing you want to evaluate.

This approach works for individual interactions with products in a given moment in time, but they don't work well for services and interventions that take place over a long period of time or what you’re looking at testing is part of a wider system of services working together to achieve joint outcomes. Some services are much more relational in their approach to achieve outcomes and support people than simple transactions.

Sometimes, we’ve tried (and failed) to extend this testing on-rails approach to longer term systemic outcomes by lengthening the horizon of these control trials to longer-term pilots. These pilots can sometimes last years only to culminate in a report that struggles to be implemented as there’s often no funding or appetite to change (hence the term ‘pilotitis’ where people became sick of this approach as they rarely went anywhere).

It's extremely demoralising to do the ‘test’ part of ‘test and learn’ if your organisation isn’t willing to do the ‘learning’ part, and crucially make the commitment to provide what’s needed to implement the results.

For me, a genuine test and learn approach is embedded into the fabric of how we approach something inside an organisation, tweaking and changing something until we get it right, repeating this cycle to a point of operationalisation with good measurement and review cycles in place. This is especially important if what we’re testing is a longer term, societal impact or something that requires multiple teams or organisations to contribute to a single outcome. Doing this successfully means we need to be able to continuously learn if we are on the right track with an idea, establishing if we need to change direction earlier than waiting for the longer term pilot results.

A support service in Craigroyston

In 2012, Snook was invited to support a fantastic leader for Edinburgh Council, Christine Mackay in the North of Edinburgh (an area I grew up in) with a new programme they wanted to run. The approach was based on a model called Total Place, a targeted area based approach that was established by the Edinburgh Partnership to ‘do what it takes’ to improve outcomes for children and families in the neighbourhood around Craigroyston Community High School.

Working with the brilliant Keira Anderson, we supported the team in bringing members of the community together to share their perspective on bringing up children in the area, living there and developing a range of ideas both run by the community and interventions by varying service providers in the area from police to social workers, housing teams to youth services and education providers.

The intention was to improve outcomes for children and young people (aligning with the ‘Getting it right for every child’ policy from the Scottish Government) and to work together as a system to achieve this, rather than disparate service providers. The project involved a multiplicity of different strands looking at local children's progression from birth to leaving school and beyond.

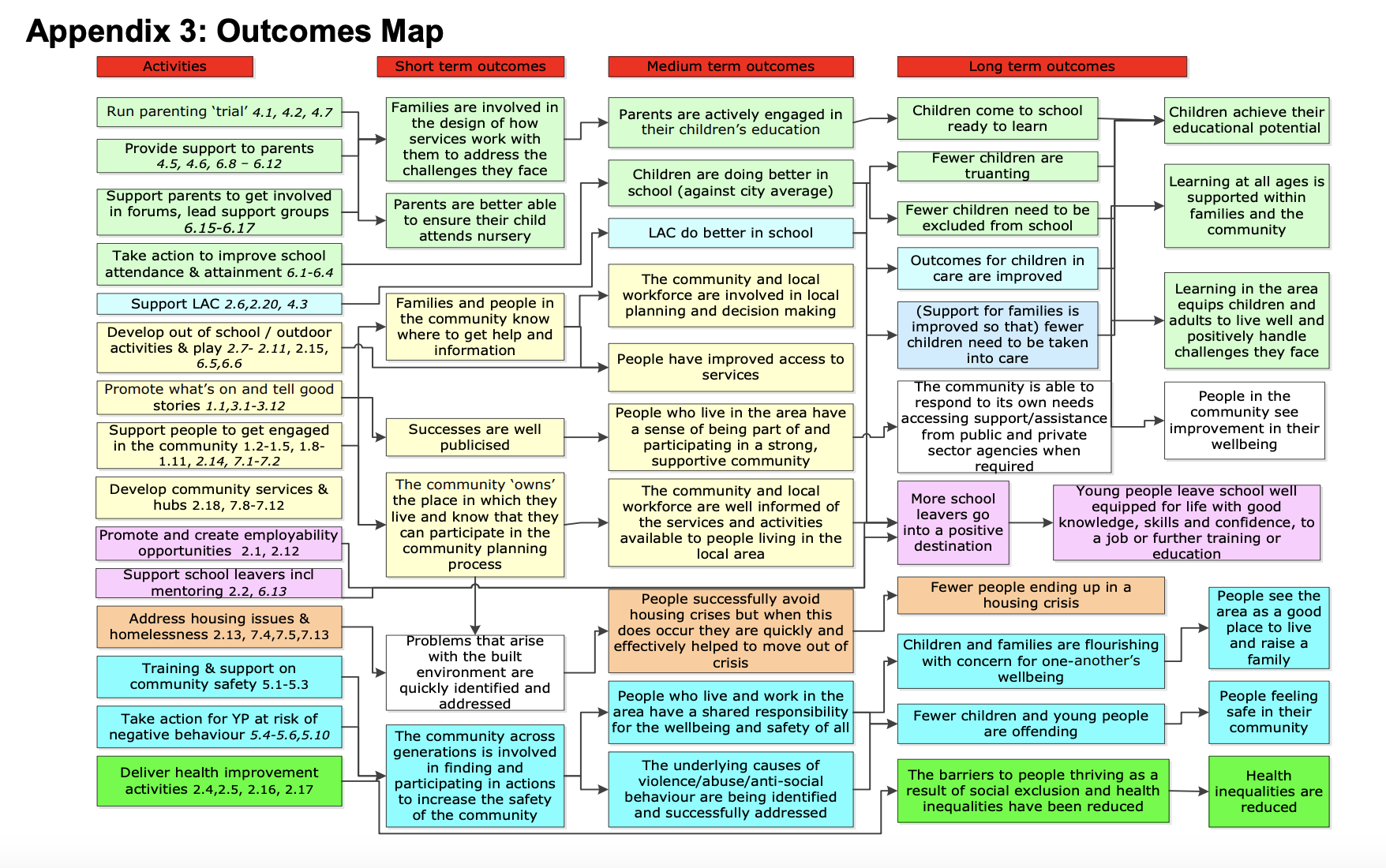

We developed principles together as a joint working group, through community co-design and engagement; like having a place to thrive, a safe place, or a place that you know. The team then developed clear outcomes with local service providers like ‘fewer children are involved in offending / repeat offending’, ‘children come to school ready to learn’, or ‘more school leavers go into education, employment and training’, with a roadmap of how each service provider would contribute to these outcomes.

When we’re aiming for long-term change, it's important to set overall outcomes in the long term, but to also identify signs of positive change or observable behaviour might show us that we’re headed in the right direction. We might call these ‘green shoots’.

Outcomes map developed with support of Evaluation Support Scotland and the local Total Craigroyston team

On this project, the team worked with Evaluation Support Scotland to create a set of indicators to help measure progress and iterate the service as we went along, recognising that meeting the outcomes would be a long term ambition and that we wanted to be able to learn more quickly and earlier to make changes if something wasn’t working. There was governance in place to ensure we reviewed progress on outcomes with regular taking stock reports and longer term reflection.

Like we did with this project, if you are adopting a test and learn approach but the outcomes you are seeking to achieve are more long term than short term, try to first identify signs of changes (indicators) in user behaviour or other metrics like market changes, sales figures, enquiries that will indicate your design is on the right path to supporting people or your organisation with your long term objective. You can also identify what you want to see more, or less of as your design is tested.

The team released quarterly reviews and looked at these early indicators like improved attainment in school. The exam results at the local High School improved in August 2012 and were the best for 10 years. On council information and support offers for families, one of our reviews included the following;

“Local midwives identified a number of difficulties in offering ante natal classes in their existing premises. The classes have now been moved to a local ‘pregnancy friendly’ community venue with some success. An additional session is now offered, which alerts parents-to-be to the range of community supports that are available in the local community and includes some basic information on brain development and attachment. Despite this improvement, midwives still struggle to attract ‘harder to reach’ parents and we are working with NHS Lothian to take forward the use of text messaging as a way of reminding parents to attend these classes.”

This piece of work was a test and learn approach at a truly systemic scale. Of course, it can be difficult to exactly pin-point when working at a systems level with a plurality of interventions, the exact lines of causation, but, this reflective and regular reviewing allowed us to ask the questions of, can we do something different? Are we meeting our outcomes?

If you’re working towards long term goals, start with some simple questions to help you think about what those goals might be;

What do we want to see more of?

What do we want to see less of?

What kind of behaviour might we want to witness/observe?

So, whether working on a macro scale like we did, or smaller more refined services with longer term outcomes, identify your indicators, those early green shoots to evaluate if you are heading in the right direction.

Testing services isn’t the same as testing code

When we’re testing services, we should be enabling teams to iteratively and continuously change direction over long periods of time. The outcome our service achieves is more important than the method we use to test, so unlike scientific tests we should be continuously iterating what we’re doing if we find something isn't working.

To do this work successfully though we need commitment, form our organisation and leadership to sign up to learn from the ideas and course changes that come from testing.

This post barely scratches the surface of methods, approaches, and mental models we can use to do this but I hope it’s useful breakdown of test and learn applied at various scales.

If you’re interested in learning more about a test and learn approach and prototyping services, get in touch or let us know if you’d like some specific training on this.

Other work you can learn from in this space;

FF Studio do some good prototyping and testing

Public Digital just released a new book, Test and Learn

The Public Service Reform: Test, Learn and Grow Programme is live